Chapter 2: The Prototype

The first step in designing a board game is to build a prototype so that you can playtest it. This is vital because there are so many changes that frequently need to be made before a game can come to market. As a simple example, your pieces might have two different colorations that are impossible to distinguish between for colorblind people, or the text on the cards might be too small for elderly people to be able to read it (this was the case with my first prototype). It’s also possible that the rules might be confusing, or even that your game might be boring. All of these problems are very important to resolve before your game hits mass production because making changes during that phase is both difficult and costly.

Fortunately, we live in what some consider the Golden Age of Prototyping. New technologies such as 3D-printing and laser-cutting make it easier than ever to build cheap high-quality prototypes of nearly anything that your mind can imagine. I immediately set to work building my prototype.

Besides the printed rules and packaging, the game would require three separate physical elements: the board, the pieces, and the playing cards. I also reluctantly made the decision to incorporate dice into the game in order to track movement points. The reason I was reluctant to do that was because of the symbolism: any game with dice implies a certain amount of randomness and one of the main selling points of this game is that (like chess) it is a heavily skill-based game with almost no randomness at all. Dice are never rolled at any point during the game and the only thing they are used for is as counters. However, the best alternative to dice would be using a 3D-printing slider to track movement. This would involve the design and manufacture of several different moving parts which would then need to be assembled to create the slider. This was an inordinate amount of work for only a mild psychological benefit so I decided to skip it during the prototyping phase. If the playtesting went well, then I could churn out some designs before the mass-production phase and get cost estimates then. For the time being, I would stick with dice.

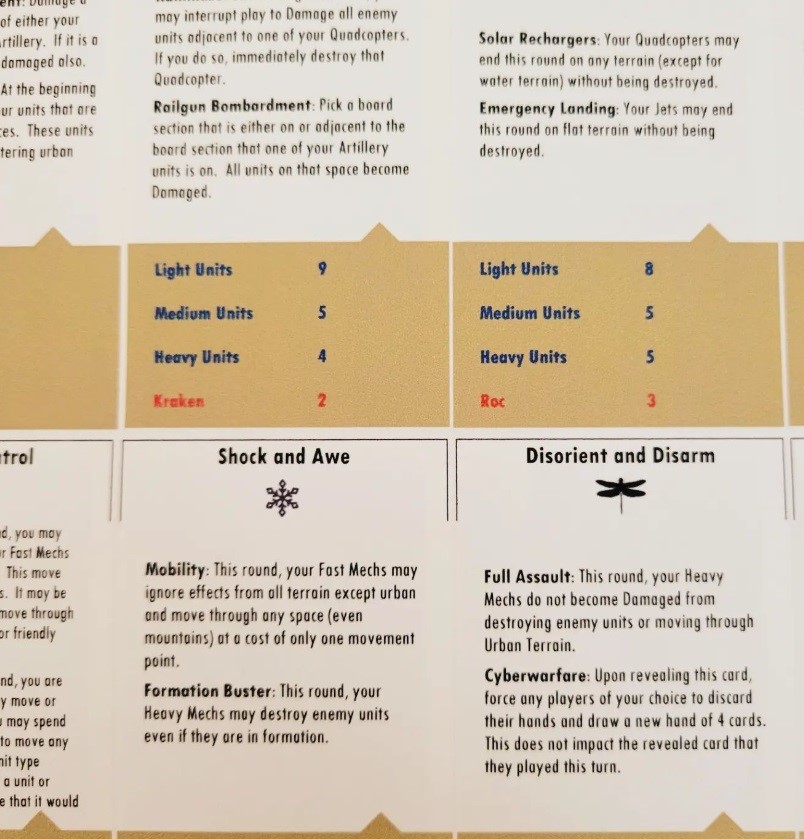

Making the first prototype of the playing cards was easy. Microsoft Word offers several convenient templates for business cards, so I simply used one of these and printed out the cards there. Most printers accept thin cardboard stock, so it was no problem to run them through the printer in one direction to print the front of the cards, then reverse the page to print out the backs of the cards. After the sheet was fully printed with the front and backs, I cut it into multiple cards. This would turn out to be the easiest part of manufacturing the prototype.

Designing the pieces would involve learning more about 3D printing. Time wasn’t an urgent factor in making the game since I estimated at least a decade before AI advancements would make competitive chess obsolete. That’s why I decided to give myself a robust understanding of 3D design and enrolled in a class at North Shore Community College (due in part to the great hiking trail right next door). The class taught us how to use Solidworks, a 3D design tool made by a French corporation named Dassault Systemes.

My Solidworks design skills turned out to be mediocre: while I had a decent technical understanding of the product, my first design (the concept model for a weaponized quadcopter drone) was clunky and blocklike with zero aesthetic appeal. Clearly I would not be the 3D design engineer for this project. However, understanding the way the system worked was invaluable. Modern 3D-printing systems are extremely sophisticated. In the past, only 3D plastic printing existed, and the pieces were extruded from a nozzle which would melt the plastic, which limited the type of design possible (since due to gravity acting upon the molten plastic, the base needed to be wider than the top of the figure). However, today there exist more sophisticated 3D printers which effectively consist of a vat full of liquid plastic. Different-wavelength lasers shoot through the vat and the pattern of interference created by them solidifies pieces of the plastic inside the vat, which means that the design is no longer restricted by gravity. There are even metal 3D printers that exist (though they cost millions and the prototypes typically have a lot of structural weakness along the Z axis). To top it off, the software packages that accompany these hardware designs have gotten very sophisticated also. For example, there are software products designed to make 3D printed structures lighter by replacing a solid interior with a hollow latticework algorithmically designed to maximize structural integrity, similar to the microscopic structure of chitin or bone. Finally, Somerville and Cambridge have a lot of “maker spaces” – hobbyist clubs where people can use shared resources like a 3D printer or laser cutter. The existence of all these technical products as well as the maker spaces where one can get easy access to them is the reason that I agree that we are in the Golden Age of Prototyping.

For the first round of prototyping, I decided to use glass tokens which I painted with different designs using Kathryn’s nail polish. Some of the tokens also used circular Ikea furniture fobs and color-coded key holders to differentiate between different unit types. The reason why these designs were so simple was because I knew that at this early stage, a lot of modifications might need to be done. Some unit types might need to be removed or added. There was no point in designing and building fancy models if they might need to be entirely replaced.

Finally, there was the board. Surprisingly, this would turn out to be the hardest part of the prototype to create. The reason why was because the Mechwar board is composed of multiple hexagonal game pieces that are connected together at the start of play to create the play area, similar to the way the setup of Settlers of Catan operates. The reason for this was to ensure that every game had a different maps, since AI learning models are great at repetitive scenarios but struggle greatly with novelty. For example, one potential Mechwar map might consist of a single massive continent, while other mechwar maps might consist of an island archipelago, a forested mountain area, or a swampy bayou. Since the board would be assembled cooperatively by the players, it would change each time. In addition to foiling AI by creating a significant element of novelty, the game mechanic of a cooperatively designed map would allow Mechwar enthusiasts to create different “scenarios” for themselves. For example, they might decide to simulate a future Chinese invasion of Japan, and create a map that looked similar to that specific area of the world.

The trouble with designing that board is that almost no board game companies create hex-based game boards. Even just explaining to a manufacturer what you want is very challenging in that regard. In the time between conception of the game and its current phase I’ve had several back-and-forth email conversations with vendors and I’m still not sure they understand what I’m looking for. Apparently phrases like “I need an interlocking lattice of hexagon shaped pieces, where each piece has a central hexagon surrounded by six other hexagons” are somehow too complicated for manufacturers to parse, particularly when English is not their first language.

I ended up designing the pieces myself using a software called Hexographer 2 (typically used to create overland maps for role-playing games like Dungeons and Dragons) to print out a board on paper. For my prototype, I printed out the paper with the terrain I had designed, glued the entire paper sheet on top of a magnetic sheet, and then overlaid that with plastic laminate to prevent the ink from fading with use. I then cut each individual piece out individually. This prototype would turn out to be very sturdy, although it was relatively expensive to create and would never be suitable for mass production.

This process of designing the prototype took approximately a year because I was also preoccupied with many real life events such as buying a condo, handling expanded responsibilities at my job in the IT industry, and on a part-time basis functioning as the lead writer for a computer game currently being designed by Game Knight Studios. However, eventually the prototype was completed and ready for playtesting.

Mechwar

| Status | In development |

| Author | MarzTec |

| Tags | asynchronous, competitive, Mechs, Multiplayer, Turn-based Strategy |

| Languages | English |

| Accessibility | Interactive tutorial |

More posts

- Chapter 7: Project PlanningJul 05, 2024

- Chapter 6: RecruitmentApr 22, 2024

- Chapter 5: The PivotMar 23, 2024

- Chapter 4: RefinementMar 16, 2024

- Chapter 3: PlaytestingFeb 21, 2024

- Chapter 1: The IdeaFeb 09, 2024

Leave a comment

Log in with itch.io to leave a comment.